Exploration – Settlement – Development

Firstly we must give credit where it is due. European exploration of the region followed on behind and directly benefited from the Aboriginal people who had inhabited and explored the area for countless years. Both explorers and early settlers looking for good land, rivers and lakes used the local knowledge of the Aboriginal community frequently. It is a debt yet to be properly repaid.

The Ginninderra area has featured large in local histories and among local historians. Ginninderra was a site of very early activity and settlement by Europeans. Fortunately there is considerable historic material available to help form a picture of the nature of this region from when this activity and settlement began. (A list of books for further reading follows).

The very first Europeans likely to have entered the area were Dr Charles Throsby and Joseph Wild who was his convict overseer. It is believed that they entered the north of the ACT while on their first foray to discover the Murrumbidgee. They did find the Yass River on this occasion. This is part of their account on a subsequent expedition describing the type of environment they found in and around the ACT,

“I am happy to report that the country in general is superior to that we passed through when with His Excellency the Governor in November last; it is perfectly sound, well watered, with extensive meadows of rich land on either side of the rivers; contains very fine limestone in quantities perfectly inexhaustible, slate sandstone and granite fit for building, with sufficient timber for every useful purpose; and, from the appearance of the country, an unbounded extent to the westward.”

This was written in 1821. Settlement quickly followed and so began the transformation of this landscape toward the picture we have today. We can be confident that as far as the Ginninderra catchment is concerned, the image of meadows surrounding rivers held true for much of this area. In fact, sheep came into contact with Ginninderra Creek very early with the coming of Ainslie and a flock of Robert Campbell’s sheep. By common account, he was directed to this area by Aboriginals he encountered between Gunning and Yass. He was looking for good grazing land. They referred to Ginnin-Ginnin-Derra. Once here, he left his flock by the creek and on the advice of an Aboriginal girl, set off to locate the area along the Molongolo subsequently taken up by Campbell.

The grazing potential of much of the Ginninderra Catchment when Campbell sent word to his nephew George Palmer describing this country. Subsequently the township of Palmerville (later Ginninderra) was founded.

Part of the Palmerville Historic Reserve (Map incorporates data that is © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) 2006).

So why settle here? It makes sense that early settlers were after the best land they could find for grazing; particularly land requiring the least effort to clear and make other improvements. The prevalence of grassy ecosystems within the Ginninderra Catchment afforded an easyr foothold for settlement. Palmer established his station at Ginninderra in about 1826, only five years after Throsby’s account.

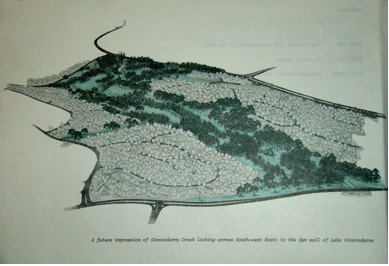

At the end of this chapter an 1832 map of Ginninderra Creek is provided. It clearly marks the creek as a chain of ponds with the words “fine grassy open forest” and “grassy open forest” written clearly. Exactly how open this “grassy forest” was not defined.

The history of grazing in the Ginninderra Catchment is a long one. Grazing practices have had a significant impact on both the land and waterways. Plants communities including healthy grasslands, slow the rate of water flowing into creeks and rivers. Water flow through these plant communities is generally more sustained and peak flow events less damaging. Grazing altered this valuable catchment function resulting in damage to both land and waterways. This can be clearly be seen in the aerial photos provided.

Grazing generally depended for a very long time on native pasture. “Pasture Improvement” has a surprisingly short history considering the level of change it has caused. This extract is from the ACT Native Grassland Strategy (also see page 17 of chapter 3);

Pastoral and agricultural development: Natural temperate grasslands in the Southern Tablelands were carved up into grazing runs from 1830. Smallscale pasture improvement began in the 1860s and clovers were first sown in the 1920s. Intensive pasture improvement involving the use of

subterranean clover and application of superphosphate was undertaken after the Second World War (Benson and Wyse Jackson 1994). This accelerated the loss of native grassland. However, some of the ACT rural lands held on short-term leases were not subject to intensive pasture improvement and retained significant components of their native vegetation cover.

The Strategies all contain insights and accounts of the way indigenous vegetation has been transformed by multiple factors. Grazing, pasture improvement, exotic species introduction and urbanization are the four major impacts that have transformed the Ginninderra Catchment to what is seen today.

Understanding about these impacts has improved. As the area given over to urbanization continues to expand, we are progressively learning to become more catchment sensitive in our planning and development We have learned to take more into account when planning and in subsequent activity from the community. For instance the plants we use have changed. Exotic trees are a feature of the creek now and loved by many for their autumn colour and dappled light. These were planted in the 1970’s and 1980’s often as wind breaks. However they grow into the creek, succour aggressively and compete with adjacent native remnants and plantings.

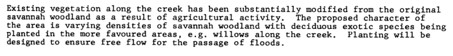

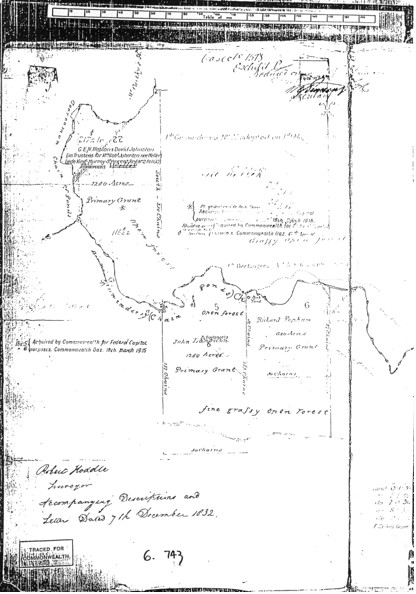

The worst culprit affecting the creek has been the Crack Willow. There are hardly any willows along Ginninderra Creek now because they were removed. Indeed, aerial photos from 1941 and 1959 also show no willows. Willows were initially thought to be stream bank stabilizers. They were introduced for that purpose and were actively spread. They proved more than capable of spreading themselves with damaging consequences. This is an exert from a National Capital Development Commission (NCDC) document written in 1978 entitled “Ginninderra Creek Open Space”. (See page 13.)

While we now have other exotic plantings, willow plantings along the creek have been removed. The idea that they would allow “free flow” has proved wrong. Moreover their legacy still remains. Willow regrowth still occurs and must be constantly controlled.

While we now have other exotic plantings, willow plantings along the creek have been removed. The idea that they would allow “free flow” has proved wrong. Moreover their legacy still remains. Willow regrowth still occurs and must be constantly controlled.

Plans for the Ginninderra Creek corridor from the NCDC document also reflect an attitude toward transforming the landscape that can now be seen as unrealistic both in terms of catchment ecology and fire risk. An artist’s impression of the creek at Evatt in the future from 1978 shows an Arcadian vision of wooded parkland in an area that the North Belconnen Landcare Group recognizes as a frost hollow which was once grassland.

Frost has killed off many planted trees and still does to this day. The lesson learned is that we must work with the landscape and the features it possesses both natural and human induced. That is not to say that some areas do not lend themselves to beautification for its own sake. We should set areas aside for this. What is important is that in managing the entire landscape we should prioritize while looking at the history of change we have brought, the problems and possibilities that exist and the best way we can use the tools at our disposal.

We are now recognising the value of our local plants to our “Bush Capital” and to the health of our catchments. This has developed to the point that many people wish to use local (provenance) stock to retain diversity within species and to take advantage of local adaptation. Some of this change has been brought on by a sense of loss and the feeling that we have to retain more of what we have left. This movement is a very powerful one.

Resources and Further Reading

1. Lyall Gillespie, Canberra 1820-1913, Australian Government Printing Service, Canberra, 1991 (Belconnen Library)

2. Lyall Gillespie, Ginninderra- Forerunner to Canberra, National Capital Printing, Canberra, 1992 (GCG Office Copy from NBLG)

3. L.F. Fitzhardinge, Old Canberra and The Search for a Capital, Griffin Press SA, Second Edition, 1983 (GCG Office)

4. Chris Newman, Gold Creek – Reflections of Canberra’s Rural Heritage, Gold Creek Homestead Working Group, 2004 (GCG Office)

5. Sites of Significance in the ACT – Volume 3 – Gungahlin and Belconnen, National Capitol Development Commission, Canberra, 1988 (Belconnen Library)

6. Peter Rimas Kabaila, Belconnen’s Aboriginal Past, Published, 1997 (GCG Office)

7. ACT Government, ACT Lowland Grassland Conservation Strategy, Action Plan No. 28, Environment ACT, Canberra (GCG Office and Supplied)

8. ACT Government, ACT Lowland Woodland Conservation Strategy, Action Plan No. 27 Environment ACT, Canberra (GCG Office and Supplied

9. Lyall Gillespie, If Ginninderra Creek Could Speak, Canberra Historical Journal No. 2 Sept 1978, Page 20 (GCG Office and Supplied)

10. National Capital Development Commission, Ginninderra Creek Open Space, Canberra, Oct 1978 (GCG Office and Supplied).

Go to the next section in Our Catchment History – “3. Comparison – Aerial Photos from 1941”